This lecture deals mainly with the ideas that went into developing Aestheticism in the nineteenth century.

As we saw last week John Ruskin paved the way by making art a serious issue, and bringing audiences in the nineteenth century to an awareness of the importance of design. Both Pater and Wilde owed much to Ruskin, though they did not share the view of the link between art and morality.

The most important book in this movement was Walter Pater's Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) which was a kind of wolf in sheep's clothing. Under the guise of a collection of historical essays he put forward a revolutionary view of art.

THE GOTHIC MODE

The early part of the nineteenth century was dominated by the Gothic style. Art, architecture, furniture all kinds of design reflected this taste, which was associated with ecclesiastical attitudes and values.

The cult for Gothic began in the eighteenth century with buildings like Walpole's Strawberry Hill.

Went through a Romantic phase in the early part of the nineteenth century, and then became associated with nationalism.

Britain, France and German all vied to have the oldest Gothic past, and this was reflected in art and design.

In Britain, Augustus Welby Pugin was one of many Gothic architects, but none was more prolific. He made a major contribution to the Catholic revival in the period.

and in a plate in one of his books supplied an illustration that showed in one image a selection of the churches he had designed.

Among the most famous of his architectural achievements was the Gothic detail for the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster. This was a magnificent example of Pugin's conscientiousness and belief in the moral superiority of the Gothic principal.

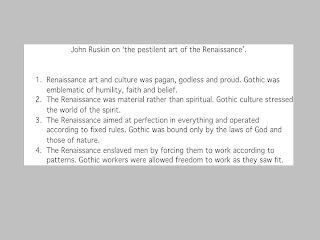

One of the most articulate champions of the Gothic style in architecture was John Ruskin, and in a chapter entitled 'The Nature of Gothic' he set out why he thought that the Gothic style was socially, intellectually and above all spiritual superiority to all other styles, notably Classical and Renaissance.

One of his most passionate admirers was William Morris, who, many years later, printed this chapter as a special pamphlet at the Kelmscott Press. In Ruskin's Stones of Venice from which this chapter was taken, the critic took the opportunity to sum up all that he found abhorrent about Renaissance art and culture.

THE REACTION TO GOTHIC: WALTER PATER

Inevitably there came a reaction to all this sanctimoniousness and piety particularly since it went in hand with a highly structured middle class moral code.

This came from Oxford and a quiet, sensitive and retiring don called Walter Pater. Suffering the unhappiness of repressed homosexuality, he was supported by the wildly amoral undergraduate, Algernon Swinburne, and the painter Simeon Solomon. He attempted to formulate a value system that offered greater freedom of mind and body in response to the repressiveness of mid-Victorianism.

He urged a re-assessment of the role of the body in art, and celebrated the pleasures of the male nude in sculpture. Pater argued that where the Gothic had denied the pleasures of the body, the Renaissance accepted and delighted in them, and in a series of essays published in the late 1860s he began to construct an alternative aesthetic theory that stressed pleasure and personal satisfaction rather than denial sanctity and duty.

These were collected together in book form in 1873 and published as The Renaissance. Few British texts were so explosive, and Pater's ideas caused a scandal. The arguments were considered to be heretical, godless, sybaritic, and self indulgent, and the coded homosexual tendency did not go un-missed.

Aestheticism had found its painters in Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Whistler, its poet in Algernon Swinburne, but now, most significantly it had found its philosopher in Walter Pater.

Pater's understanding the word 'Renaissance' was fundamentally different from Ruskin and his contempoaries.

When he spoke of the new Renaissance 'freedoms' achieved by the late middle ages, he was really talking about the mid-nineteenth century.

Pater was one of the first critics to discover the painting of Boticelli, which subsenquently became strongly associated with Aestheticism. The appearance of langour and disinterestedness in The Madonna of the Magnificat Pater made into an ideological virtue.

Pater through his careful attention to language and it aesthetic beauty made art-criticism a fine art. Here, he invokes Leonardo's Mona Lisa by expressing something of the subjective mood that the painting induces in the viewer.

THE REACTION TO GOTHIC: OSCAR WILDE

Oscar Wilde, who was taught by Pater in Oxford, took his tutor's ideas one stage further. As in the case of Pater, homosexual desire helped to fuel his aesthetic, but where Pater was covert, shy and retiring, Wilde was overt, bold and theatrical. Like Pater, Wilde raised the status of English prose which, in his hands aspired to the condition of poetry. The opening of A Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) provides a good example.

Where Pater used history to embed his own attitudes and values, Wilde employed comedy. He was often poked fun of in the press.

But he employed paradoxes and odd aphorisms as a means of aesthetic and social criticism. His Preface to his novel A Picture of Dorian Gray is famous for this technique,

and his witty, trenchant and acerbic comments on Victorian society have remained fresh and lively.

In the end, Wilde had to go before the wallpaper. He died in Paris in 1900, and when in body was moved to the cemetery in 1909 the sculptor, Jacob Epstein was commissioned to create a monument for him.