Sunday, 20 February 2011

Early Aesthetic Painting

In the late 1850s painters, led by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, began to develop works that had no precise narrative or moral purpose. They were often criticised for their vacuousness or for their immoral sensuality.

Enter James MacNeill Whistler

Whistler, American in origin, came from studying in France, to settle in London in the early 1860s. He took a house in Chelsea close to Rossetti with whom he set up an uneasy friendship. He began a series of enigmatic pictures often with musical titles.

|

| Symphony in White no. 1: The White Girl (1862) |

|

| Symphony in White no. 2: The Little White Girl (1864) |

The Return of the Nude

In the 1850s the nude had largely disappeared from the walls of contemporary art exhibitions, but mainly as the result of the work of Aesthetic painters, it returned to artistic practice in the 1860s.

One of the primary sources of inspiration was the rediscovery amongst this new group of painters of the work of Botticelli. It was not long before the adjective 'Botticellian' was applied to aesthetes with modern sophisticated tastes.

One of the primary sources of inspiration was the rediscovery amongst this new group of painters of the work of Botticelli. It was not long before the adjective 'Botticellian' was applied to aesthetes with modern sophisticated tastes.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (c.1486) |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Here is a list of books that might be helpful in giving more detailed information about the Aesthetic Movement. Most are rather specialised other than Aslin and Lambourne.

Aslin, Elizabeth. The Aesthetic Movement : Prelude to Art Nouveau. London: Elek, 1969.

Bullen, J.B. The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire in Painting, Poetry and Criticism. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Dellamora, Richard. Masculine Desire : The Sexual Politics of Victorian Aestheticism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Evangelista, Stefano-Maria. British Aestheticism and Ancient Greece : Hellenism, Reception, Gods in Exile. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Gaunt, William, and Robin Spencer. The Aesthetic Movement and the Cult of Japan : [Exhibition] 3-27 October 1972. London, 1972.

Lambourne, Lionel. The Aesthetic Movement. London. London, Phaidon, 1996.

Livesey, Ruth. Socialism, Sex, and the Culture of Aestheticism in Britain, 1880-1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. After the Pre-Raphaelites : Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

———. Art for Art's Sake : Aestheticism in Victorian Painting. New Haven, Conn. ; London: Yale University Press, 2007.

Psomiades, Kathy Alexis. Beauty's Body : Femininity and Representation in British Aestheticism. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Schaffer, Talia, and Kathy Alexis Psomiades. Women and British Aestheticism. Charlottesville ; London: University Press of Virginia, 1999.

Aslin, Elizabeth. The Aesthetic Movement : Prelude to Art Nouveau. London: Elek, 1969.

Bullen, J.B. The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire in Painting, Poetry and Criticism. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998.

Dellamora, Richard. Masculine Desire : The Sexual Politics of Victorian Aestheticism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990.

Evangelista, Stefano-Maria. British Aestheticism and Ancient Greece : Hellenism, Reception, Gods in Exile. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Gaunt, William, and Robin Spencer. The Aesthetic Movement and the Cult of Japan : [Exhibition] 3-27 October 1972. London, 1972.

Lambourne, Lionel. The Aesthetic Movement. London. London, Phaidon, 1996.

Livesey, Ruth. Socialism, Sex, and the Culture of Aestheticism in Britain, 1880-1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Prettejohn, Elizabeth. After the Pre-Raphaelites : Art and Aestheticism in Victorian England. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

———. Art for Art's Sake : Aestheticism in Victorian Painting. New Haven, Conn. ; London: Yale University Press, 2007.

Psomiades, Kathy Alexis. Beauty's Body : Femininity and Representation in British Aestheticism. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Schaffer, Talia, and Kathy Alexis Psomiades. Women and British Aestheticism. Charlottesville ; London: University Press of Virginia, 1999.

Saturday, 19 February 2011

LECTURE 2: Burning with a hard, gemlike flame: the high priests of Aestheticism: Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde

This lecture deals mainly with the ideas that went into developing Aestheticism in the nineteenth century.

As we saw last week John Ruskin paved the way by making art a serious issue, and bringing audiences in the nineteenth century to an awareness of the importance of design. Both Pater and Wilde owed much to Ruskin, though they did not share the view of the link between art and morality.

The most important book in this movement was Walter Pater's Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) which was a kind of wolf in sheep's clothing. Under the guise of a collection of historical essays he put forward a revolutionary view of art.

THE GOTHIC MODE

The early part of the nineteenth century was dominated by the Gothic style. Art, architecture, furniture all kinds of design reflected this taste, which was associated with ecclesiastical attitudes and values.

The cult for Gothic began in the eighteenth century with buildings like Walpole's Strawberry Hill.

Went through a Romantic phase in the early part of the nineteenth century, and then became associated with nationalism.

Britain, France and German all vied to have the oldest Gothic past, and this was reflected in art and design.

In Britain, Augustus Welby Pugin was one of many Gothic architects, but none was more prolific. He made a major contribution to the Catholic revival in the period.

and in a plate in one of his books supplied an illustration that showed in one image a selection of the churches he had designed.

Among the most famous of his architectural achievements was the Gothic detail for the new Houses of Parliament at Westminster. This was a magnificent example of Pugin's conscientiousness and belief in the moral superiority of the Gothic principal.

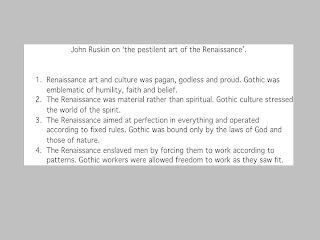

One of the most articulate champions of the Gothic style in architecture was John Ruskin, and in a chapter entitled 'The Nature of Gothic' he set out why he thought that the Gothic style was socially, intellectually and above all spiritual superiority to all other styles, notably Classical and Renaissance.

One of his most passionate admirers was William Morris, who, many years later, printed this chapter as a special pamphlet at the Kelmscott Press. In Ruskin's Stones of Venice from which this chapter was taken, the critic took the opportunity to sum up all that he found abhorrent about Renaissance art and culture.

THE REACTION TO GOTHIC: WALTER PATER

Inevitably there came a reaction to all this sanctimoniousness and piety particularly since it went in hand with a highly structured middle class moral code.

This came from Oxford and a quiet, sensitive and retiring don called Walter Pater. Suffering the unhappiness of repressed homosexuality, he was supported by the wildly amoral undergraduate, Algernon Swinburne, and the painter Simeon Solomon. He attempted to formulate a value system that offered greater freedom of mind and body in response to the repressiveness of mid-Victorianism.

He urged a re-assessment of the role of the body in art, and celebrated the pleasures of the male nude in sculpture. Pater argued that where the Gothic had denied the pleasures of the body, the Renaissance accepted and delighted in them, and in a series of essays published in the late 1860s he began to construct an alternative aesthetic theory that stressed pleasure and personal satisfaction rather than denial sanctity and duty.

These were collected together in book form in 1873 and published as The Renaissance. Few British texts were so explosive, and Pater's ideas caused a scandal. The arguments were considered to be heretical, godless, sybaritic, and self indulgent, and the coded homosexual tendency did not go un-missed.

Aestheticism had found its painters in Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Whistler, its poet in Algernon Swinburne, but now, most significantly it had found its philosopher in Walter Pater.

Pater's understanding the word 'Renaissance' was fundamentally different from Ruskin and his contempoaries.

When he spoke of the new Renaissance 'freedoms' achieved by the late middle ages, he was really talking about the mid-nineteenth century.

Pater was one of the first critics to discover the painting of Boticelli, which subsenquently became strongly associated with Aestheticism. The appearance of langour and disinterestedness in The Madonna of the Magnificat Pater made into an ideological virtue.

Pater through his careful attention to language and it aesthetic beauty made art-criticism a fine art. Here, he invokes Leonardo's Mona Lisa by expressing something of the subjective mood that the painting induces in the viewer.

THE REACTION TO GOTHIC: OSCAR WILDE

Oscar Wilde, who was taught by Pater in Oxford, took his tutor's ideas one stage further. As in the case of Pater, homosexual desire helped to fuel his aesthetic, but where Pater was covert, shy and retiring, Wilde was overt, bold and theatrical. Like Pater, Wilde raised the status of English prose which, in his hands aspired to the condition of poetry. The opening of A Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) provides a good example.

Where Pater used history to embed his own attitudes and values, Wilde employed comedy. He was often poked fun of in the press.

But he employed paradoxes and odd aphorisms as a means of aesthetic and social criticism. His Preface to his novel A Picture of Dorian Gray is famous for this technique,

and his witty, trenchant and acerbic comments on Victorian society have remained fresh and lively.

In the end, Wilde had to go before the wallpaper. He died in Paris in 1900, and when in body was moved to the cemetery in 1909 the sculptor, Jacob Epstein was commissioned to create a monument for him.

Friday, 18 February 2011

LECTURE 3: Dressed to Kill

In Tissot's 1877 picture, fashionable girls on the deck of the Calcutta are dressed in high fashion with bustles that stress their bottoms. In the 1881 picture by Frith of the private view at the RA the women on the right are dressed in quite a different way.

They are dressed in Aesthetic costume, and they look on admiringly at Oscar Wilde who discourses on the paintings. The Frith demonstrates the extent to which Aesthetic dress had become accepted, if eccentric, in polite society as members of the Establishment, poets, writers and politicians mix with the new brand of Aesthete. One of the leaders of this movement was Wilde's wife, Constance.

They are dressed in Aesthetic costume, and they look on admiringly at Oscar Wilde who discourses on the paintings. The Frith demonstrates the extent to which Aesthetic dress had become accepted, if eccentric, in polite society as members of the Establishment, poets, writers and politicians mix with the new brand of Aesthete. One of the leaders of this movement was Wilde's wife, Constance.This had not always been so, and during the previous twenty years women had been constructed, shaped and changed in a number of different ways. The principal agent of female shape had been the corset aided by the crinoline.

The corset pinched in the waist and pushed up the breasts.

whereas the crinoline opened up widely from waist to floor exaggerating the narrowness of the waist.

From the early 1850s there had been a great deal of controversy about the nature of tight lacing, and many men and women insisted that it was dangerous to the health.

This was often parodied as a form of slavery to high fashion.

But the fashion plates in magazines continued to promote both the crinoline and tight-lacing.

In the 1840s and 1850s the ideal of female beauty was exemplified by the small mouth, large brow, simpering expression, rounded arms, breasts pushed up, and waist pulled in.

The reaction to this style came from the Aesthetes, and was pioneered by Dante Gabriel Rossetti who helped design and choose the material for some of the clothing of Jane Morris. A series of photographs of Jane taken in Rossetti's garden in 1865 exemplify this new style.

The contrast with high fashion is clear. The stress in Aesthetic costume is on freedom of movement. There is no crinoline and the body can move easily. There is no corset and the dress is tied round the waist. The wide sleeves allow freedom of movement to the arms.

In the early 1860s Whistler dressed his mistress Jo Hiffenran in similar clothing, which again contrasts with fashionable dress in this female group by Monet.

The origins of Aesthetic design can be found in the 1850s, and in the clothing adopted by the Pre-Raphaelites for females in Gothic designs and compositions.

The clothing in Rossetti's Blue Closet derives from a number of illustrated histories of dress that were available to him and to the Brotherhood at this time.

Similarly this picture of Jane Morris as Guenevere by William Morris suggests a similar influence:

But there was another influence:

Barbara Leigh-Smith, reformer, early feminist wrote early in her career on the evils of tight lacing. As students she and her close friends (much to the horror of their parents) refused to wear corsets, and on a walking holiday in Germany she drew herself and those friends in the new un-corsetted outfits.

Barbara Leigh-Smith took up the young Elizabeth Siddal around 1853 when Lizzie was ill and convalescing in Hastings. Lizzie also adopted this easy, informal manner of dress which was ideal for a female painter who needed to move around the studio. The drawing is by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

From quite a different quarter came another influence on the development of Aesthetic dress. The Pattle sisters, were rich beautiful, French educated and born in India. One of them, Sarah Princep, created an artistic salon in Little Holland House, London in the mid-1850s. All the sisters dressed in an eccentric and extravagant way with flowing dresses, no corsets and no crinolines.

Sara not only invited the Pre-Raphaelites, Ruskin, Browning and other members of the literary and artistic world to Little Holland House, she also had parties, and adopted Jane Morris in 1859 just as she was about to become William Morris's.

Edward Burne-Jones who also visited the Princeps painted Green Summer at the Red House, home of the Morris's, where the women are all wearing unconventional Aesthetic clothing.

By the end of the 1860s Jane Morris had become identified with this outlandish way of dressing and startled Henry James when he was introduced to her and to Morris in their London home.

The crinoline vanished and was replaced by the bustle, but the contrast between that style and Aesthetic dress is now clear. But more than this, high fashion was seen as conformist, Aesthetic dress as non-conformist, bohemian and even immoral. Loose clothing suggested loose morals.

In this poster for the music for an Aesthetic parody, The Colonel, the woman is clearly displaying her body in her loose clothing in a provocative and inappropriate manner.

By the 1890s, however, the middle-classes had adopted the style as a mark a particular kind of elegance, and through the agency of firms like Liberty, Aesthetic dress became not a mark of bohemianism but a sign of sophisticated taste.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)